An interview with Jamila Abass, CEO and co-founder of M-Farm

The winner of the first IPO48 Nairobi event in November 2010, M-Farm is an all-female mobile / web start-up that seeks to improve the economic condition of Kenya’s farmers. Using a basic SMS interface, M-Farm helps farmers by providing them with access to current market prices, aggregating their needs into discount orders with suppliers, and giving them direct, collective access to both regional and export markets for their products.

The young company has faced many challenges over the past 9 months, not the least of which was a change of their short code by mobile service providers after four months in operation that necessitated an awareness and retraining campaign for their existing customers (the current short code is 3535 in case you’re in Kenya and want to use M-Farm).

Despite a host of steep learning curves, challenges and setbacks familiar to many startups, M-Farm is currently used by more than 2,000 farmers. M-Farm is planning to target five additional regions for marketing and awareness campaigns starting later this month, and have a goal of adding 10,000 more users by the end of the year.

I met with CEO and co-founder Jamila Abass, a 27-year-old Kenyan Somali from Wajir, at this year’s IPO48 event and asked her about life since the launch, lessons learned, her perspectives on the Kenyan tech scene, and her thoughts on the promise of mobile digital technologies for development.

What first got you interested in technology and computing?

Well, my path was a bit different. My dream was always to become a neurosurgeon, but that never happened. I got a scholarship to study in Morocco, and I thought it was to join the medical school, but we got there, we found out that of the seven of us who had received the scholarship, only one of us would get to study medicine.

I had to look for other options. One of my friends from Sierra Leone was studying computer science, and he encouraged me and showed me what computers can do. That’s how I ended up getting a bachelor’s in software engineering. I wasn’t prepared for it at the start, but I’m really, really glad that sometimes nature dictates what we are supposed to do.

It’s so exciting, the little effort you put into technology, and how it can change people’s lives. The beauty of it is that you can do whatever you have to do anywhere and anytime. As a technologist, you can come up with something that touches a lot of people’s lives.

How did you first get involved with the other women of M-Farm?

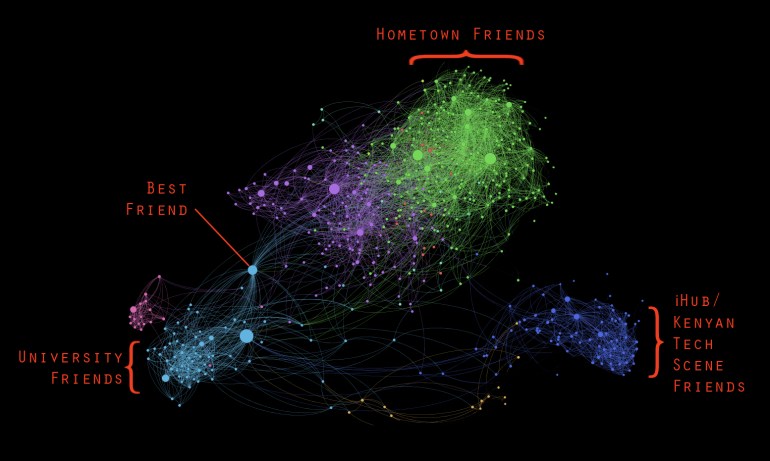

I was working with a company called Kenya Medical Research Institute, as a medical records… developer? I’ve even forgotten what I used to do! All I remember is that I used to develop medical records systems. One of my colleagues told me about iHub being put together, and the first thing I saw on the blog was something about AkiraChix – this group of ladies who came together to promote the presence of ladies in the Kenyan IT community. I was wowed… I never knew such a thing existed. I emailed them and they welcomed me to the iHub. When I saw this place being built, I realized there was a big potential here. When iHub was launched, the IT boom was just crazy. It was a hard decision, but I quit my job and joined the iHub as an intern.

You see how they have all the daily newspapers over there in the rack on the wall? Me and Susan Oguya (M-Farm’s CTO) noticed that the farmers were complaining – at one point you’d see at least three articles every day talking about different complaints. They don’t have price information, the middlemen just come and dictate what the prices are – they’ll come and tell the farmers, ‘the markets are really flooded, there’s overproduction, so you can’t get good prices. You either sell it to me cheap, or you’re not going to find anyone who will buy.”

People were just manipulating the lack of transparency in the market and the farmers were the ones losing. So we linked the farmers’ complaints to a lack of information. We said, ok, what do we know how to do best? Delivering information, right? So how can we use that knowledge to deliver that information to the farmers? As we were brainstorming it, IPO48 was announced. Then we got more serious about our idea, and decided we were going to present it.

M-Farm’s winning final pitch at IPO48 Nairobi in 2010:

During the 48 hours, Susan, Linda Kwamboka and I and two other ladies kept on working on the idea. We developed the business plan, the prototype, everything within the 48 hours, and we won. I remember that night, I didn’t believe we won. When they mentioned our names, you know all that excitement that you really won, and that you wanted all that to pass through, launch it, and become a business… we all left out jobs to make this business work. Then here you are – you’ve got the opportunity to make that happen. So it was so overwhelming, those first three day, it was crazy. Nobody knew us before, but all of a sudden within three days of competition we become a local star. OK… what next?

Was winning a blessing or a curse?

Can I say a combination of both?? Most of it was a blessing, and some of it was a curse. The blessing was we got free publicity and free marketing. Almost everyone who’s a blogger here talked about us, so the word got out very quickly. Many NGOs and farmers’ groups got to hear the news quicker than we thought. So that was the big blessing. The second blessing was we got many people interested in the idea, and many more people beyond our small team believed in the idea, so we got support from the whole community.

The curse was, sometimes you’re just too new, you don’t know what to do with what you have. You have this big anxiety inside of you. You don’t know how to control it and it overpowers you. You just won the investment prize, but that takes some ownership of your company before you have any concept about valuation, legal or financial issues… the list goes on and on.

Also, having all these people who know about you and are interested in your idea, it really becomes difficult to select who to talk to and who not to talk to. We didn’t know how to selectively choose who to set up meetings with. So the first three months were non-stop meetings, everybody wanting to talk to us, everybody wanting to meet us. Some days I would spend all day replying to emails… some of our time was simply misused.

What’s been the most difficult part of developing a viable business in the year since you launched?

The most difficult thing was getting the business model right. When you’re sitting in your office, you think that your business model is really set. It isn’t. When you go out into the real world, launch the product and hear what the people who are supposed to use the product say, everything changes.

When you’re an entrepreneur, you really wish that people will really accept the idea that you brought forward, and they will buy the service from you and you’ll start making money quickly. But when you have to spend six more months coming up with new business models, testing it out, coming back, changing everything… you have to be very, very patient for that kind of work. So that’s been a really big challenge.

How would you describe the change from the business model you started with to the one you have now?

The change isn’t so drastic, but things that we thought would work easily didn’t work out. For example, we started with the business model where the farmers would use the service to collectively buy farm inputs like seeds and equipment. Having aggregated the farmers’ needs, we would link them with a supplier so they got a competitive price and that would make their lives easier. What we found is that if you’re not helping the farmers sell their produce, then they don’t have the money to investing in the planting cycle.

For us, we planned to start our relationship with the farmer from the time they put the seed in the ground to the time they harvested the crop. Apparently, it needs to be the other way around. You start from the time they harvest – that’s the beginning of the business cycle. If you don’t help them sell, they don’t have the money during the planting time, and then you can’t sell any other services to the farmer. So you have sell for them first, and do the rest afterwards.

Next, we thought the pricing information was going to be such a genius idea, but later on we found out that giving them price information alone is not enough. OK, I so you’ve given me the information, right? If I don’t have any other way of finding out what to do with this information, then you haven’t changed anything in my life. We later on found out that information alone isn’t enough. Information needs execution – without that you’re not changing anyone’s life. The way our ideas worked was almost upside down. We had to start from the selling, then to the buying, then to providing other information that they would have required.

What’s the biggest challenge for building brand awareness in a place like Kenya?

It depends on whom you’re targeting. If you’re targeting the urban dwellers, it’s really easy – TV, radio and newspapers. If you’re targeting the rural areas like we’re doing, then things take a different direction. It would be a waste of money if we started doing radio campaigns or TV or newspapers, because the people that we’re targeting won’t get the news. The challenge is finding out the proper channel to use to deliver this information.

We approach the local leaders in the rural area, tell them what M-Farm can and cannot do, and if they buy the idea, they’ll spread it to the rest of the people. That was the difficult thing, because using people as your agents to spread the word is much more difficult than running an ad campaign on radio or TV. The local leaders are trusted much more than radio or even TV, so even though the process is slow, it’s also short in a way. People will believe it because they heard about it from the local chief, the local counselor or something like that – they need someone they can trust in the process. The challenge in that approach is in scaling that up quickly and delivering the news to the people who are supposed to hear it.

How do balance the needs of running a business with the need to keep up on IT and programming trends?

Most of the time I feel outdated, especially because I also have to run a business. When you’re running a business, you can’t do everything by yourself. When you have customers waiting on you, you can’t say, ‘you know what? Let me just finish up what I’m doing now, and then I’ll come back with the software and I’ll do it myself.’ So you have to trust other people to do things. For me that means depending on other people to do the development while I run the business. That’s why sometimes I find myself feeling so backwards that when I try to look at code that other people have written, I just get lost.

What websites do you use to keep yourself updated?

Net.tuts – I like that one because they summarize everything in a sweet way, and you can easily know what’s going on. And I also like Business Insider and Tech Crunch, even though they don’t write much about programming, at least they keep you in the loop about what’s going on in the IT world.

What do you find exciting about the tech scene in Kenya?

Now we have a place we can call home in the iHub – a place where we share ideas about the problems the tech community is facing, and we have representatives who can talk about it and have our voices heard. Before having structures like the iHub and the m:lab, and the other incubation centers that exist, however loud you shouted, nobody heard you. But now you can sit together, talk about something, and all of a sudden you’re speaking the same language.

With that you get to do more things. For example, you never, or at least very rarely used to walk in somewhere and meet the head of Google in Kenya for example, but that’s happening now. You meet people you’d otherwise never have the chance to meet.

Nowadays you hear lots of people in the tech scene in Nairobi using an elevator pitch. Before, nobody even knew what that was – why would you want to speak to an elevator? So we’re bringing all the stakeholders under one roof, which rarely happens. We also have more people focusing on the social problems that Kenyans are having. We have many creatives and entrepreneurs coming up with solutions, so two things happen: the entrepreneur gets to do a project that they really enjoy and you get to address a social problem that’s affecting millions of people.

Many of the young people have been complaining about the lack of jobs, so now you’re creating jobs for yourself and other people at the same time. The other thing is information is power. All of a sudden, you’re able to put your point across and people understand what you mean. We have the means of delivering a message that we didn’t have before. In the past, how many people would have a mobile that’s internet enabled, or a mobile that could access data? Right now almost everyone does, and that’s a big change.

How is the mobile device changing Kenya?

Traditionally people would use it for calling and for SMS, just to communicate with their loved ones. Now they’re using it for business. So the more people you get using their mobile phones for business, the more opportunities developers will get to develop applications that target specific groups of people. The developer is making money by creating an app, the end user is saving money by using the app.

It’s connecting people as well, for example, most schools in Kenya don’t have quality content to present to their students – they have qualified teachers, but they don’t have the books. If they could use a mobile phone to see what a teacher in a more sophisticated school has written or used, or have s student in the heart of Turkana (the poorest region in Kenya, with a poverty rate of 94%) share a note with a student in Nairobi who has more money to attend a good private school, then sharing knowledge becomes easier.

I could also share information that is negative, but the point is, people get access to things they’ve never experienced before. Just like for myself, before I knew how to use Google, my thinking was limited to what I learned in books, but now my thoughts are broadened just because I can access something written by a professor at Oxford.

Where do you want do go with all of this? Where do you see yourself in the future?

That’s really a big question. I’ve always been passionate about empowering people. I grew up in a place where accessing information was almost impossible, a place that almost everyone has neglected. So I grew up knowing that someone has to make a difference, to go out and get the skills to bring change to the place where I was born. There’s a lot of negative energy coming out of that place, “oh the government neglected us, oh we don’t have rain, we have these droughts.” We don’t have people sitting down and thinking of what we already have and thinking about how to use those things in a positive way. That’s the person I want to be.

This is very interesting. Bringing IT and farmers togather! Very genius young people! I would like them take one-step forward. It seems that they are helping large or medium scale farmers who have access to markets.

Jamila Abass mentioned that they are also giving farmers information on weather updates due to drought. So, I would like them develop other models on helping the most vulnerable farmers to climate change, the small holder farmers. I guess illiteracy is relatively higher in this group of farmers and their use of technology will be limited!

Small holder farmers have less or no access to markets. Their production is mainly used for houshold consumption. They have no time to search for a good price for their small amount of products. These are the most vulnerable farmers.

Keep working, Jamila and M-Farm group

like them develop other models on helping the most vulnerable farmers to climate change