“It’s not that transparent, but Kenya is fast becoming a real estate mecca for pirates looking to stash their booty.”

Fast Company: Laundered Somali Pirate Money a Boon for Kenyan Arrr-chitecture

“In neighboring Kenya, new buildings are rising, their construction fueled by piracy money in Nairobi’s Eastleigh neighborhood, where many Somali immigrants live.”

NPR: Somali Pirates Take The Money And Run, To Kenya

“According to Bruno Schiemsky, an independent consultant on piracy, ‘It might have the consequence that property prices [in Kenya] inflate artificially because of the sheer amount of money the pirates have.'”

France 24: Piracy money inflates Kenyan property market

Is pirate money fueling the booming economy in Eastleigh? The short answer, probably not.

A common non-Somali explanation for the visible success of Eastleigh hinges on supposed flows of illicit funds tied to ransom payments to Somali pirates. For some in Kenya and abroad, the idea of Somali refugees and diaspora creating a thriving commercial center without the help of pirate booty seems implausible. As reported in a Huffington Post article titled, Pirate Ransom Money May Explain Kenya Property Boom, “The hike in real estate prices in the Kenyan capital has prompted a public outcry and a government investigation this month into property owned by foreigners. The investigation follows allegations that millions of dollars in ransom money paid to Somali pirates are being invested in Kenya, Somalia’s southern neighbor and East Africa’s largest economy.”

While security issues aren’t really the focus of an ethnographic project such as ours, it’s a good question to address when studying the economic rise of Eastleigh as part of a larger focus on trust and trade networks among Somali diaspora. But how, precisely, do you go about answering this kind of question? Somali shop owners are understandably dismissive of such ideas, claiming that while some piracy funds might find their way into the local economy, ransom money certainly isn’t the driver of growth here. For those predisposed to see a pirate in every Somali closet, such denials are to be expected. Those involved in legitimate local businesses, however, understandably see it as an implicit accusation of criminality and disregard for the hard work they do to build and maintain profitable enterprises. Treating source communities with the respect they deserve while still maintaining a critical and objective attitude is an important balancing act to maintain if you want to establish credibility and trust as a researcher.

For researchers, there are also potential security issues that have to be taken into consideration while working in the field. An interview with one of the largest local property developers in town ended with him warmly shaking our hands and saying, “Good luck with your research. I hope you survive.” That proved rather effective at instilling a certain amount of paranoia, as being known as the white guys poking around a town like Eastleigh asking everyone about pirates and terrorists probably isn’t the best idea.

As an additional word of caution for future researchers, people here are relatively tech savvy despite outward appearances, and it’s common to have interview subject Google your name or befriend you on social networks after a brief meeting. Two of the defining features of the digital age are transparency and permanence, and researchers should be aware that locals will quickly find out who you are and what you’ve worked on before. Managing both local perceptions and your digital identity are issues that need to be taken quite seriously for those who want to securely gather quality information in the field.

Considering the evidence

Looking at local investment figures and databases of tax filings would be a start to unraveling the piracy question, if only such data was widely available here. Reliable figures in many areas such as census and economic data are difficult, if not impossible to obtain in Kenya, as political sensitivity, bureaucratic indifference, and informal local business practices combine to make the collection of good data a challenge.

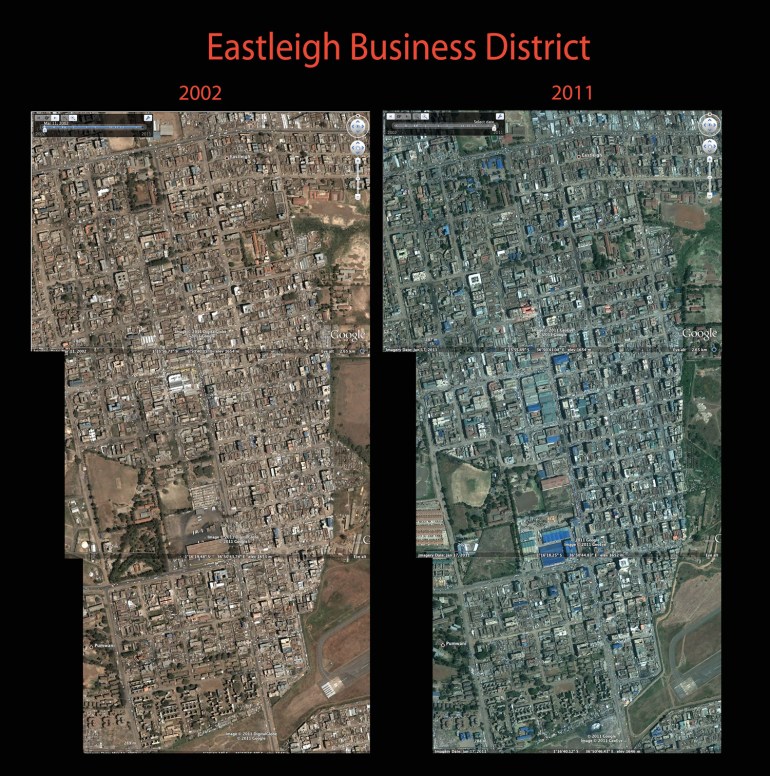

Disclaimers and limitations aside, perhaps a brief look at some data in the public domain can shed light on the issue. One rather rough but interesting way to speculate on the impact of piracy funds in an economy like Eastleigh would be to create our own estimates and try to correlate that with available data on piracy. Short of polling the entire town or getting hopelessly mired in the red tape of the tax office, one approach could be the use of Google Earth’s historical imagery feature to track changes to the local landscape over time.

With some screen captures and two rather tedious hours spent counting buildings in 21 different satellite views of Eastleigh, I came up with a rough estimate of historical development that looks something like this:

A serious analysis would need to look at comparable square footage of new commercial and residential space, but this rough view can give some indication of market trends.

One feature that stands out is that Eastleigh’s historical development doesn’t correlate at all with trends in the global financial markets. As an experienced real estate portfolio manager (i.e., my girlfriend) told me, “It means they’re relatively isolated from the global markets. They’re not depending on banks to finance development, so equity takes the form of cash in this market.”

A quick check of piracy figures would show that while the 2004 development in Eastleigh would not be explained by piracy, 2009-2011 development does nicely correlate with the upsurge in piracy in the Gulf of Aden and Indian Ocean:

Piracy figures from the Blue Mountain Group: http://www.bluemountaingroup.co.uk/maritime-security/piracy-statistics.asp

Mystery solved? Bearing in mind that ‘correlation does not imply causation’. (if it did, we could also link piracy to say, global warming), we should take a closer look at the actual funds involved. Would the volume of ransom money be adequate for the level of development seen in Eastleigh?

It’s not how much you make, but how much you keep

Some estimates claim that approximately $200m was paid in ransom money to Somali pirates in 2010 (up from just $80m in 2008), though that’s gross revenue, not profit. Piracy is, after all, just another business, and an extremely competitive one at that. A considerable chunk of that revenue would need to be pumped back into the business via wages, equipment, weapons, ammunition, boats, servicing facilities, multi-day wedding parties with nonstop dancing and goat meat, etc.

With one interesting analysis claiming that profits after expenses might run $120m per year and another estimating that financiers and sponsors receive 50% of the ransom revenues, then perhaps $100-120m became available last year to those in the piracy trade with investment savvy. Could all that money find a home in Eastleigh? It’s possible, but unlikely for a few reasons. First it would assume that all piracy funds from the plethora of reported investors would come to Eastleigh, rather than Dubai, Djibouti, Yemen, or within Somalia itself on homes, vehicles, security, and so on. Secondly, it would assume than nothing is reinvested into the piracy business to finance future operations. Assuming that no legitimate enterprises in this region could offer returns on investment to rival piracy, real estate development in a place like Eastleigh might only be a attractive for more conservative investors, or as part of a diversification strategy. More importantly, such sums would constitute a fraction of cash inflows for an area that may be drawing upwards of a billion dollars a year in total investment.

There’s also the issue of timing. The average period between capture and ransom payments has been growing along with seizures and ransom demands. A pirate crew seizing a cargo ship might negotiate for three to six months before releasing their crew, with the longest hijacking lasting more than a year. On the construction side, one developer told us that getting a new project through the permitting process can take upwards of a year (and no shortage of bribes), while work on a large structure might take 18-24 months. Assuming that new construction was financed up to two years before completion, and ransoms paid up to six months after hijackings, this could shift the graphs to indicate that piracy has a trailing rather than direct correlation with commercial development in Eastleigh.

If not piracy, then what?

If development capital doesn’t come from piracy, where does it come from? Though we’ll explore a longer list of alternative hypotheses in the next post, it’s worth briefly mentioning the volume of remittances, i.e., funds sent home by Somali diaspora working abroad. Even a casual look at the figures indicate that the small funds sent to friends and relatives from paychecks and savings abroad add up to substantial capital flows. Current data on global remittances place the total figure for 2010 at approximately $440bn, with global remittances to Somalis both here and in Somalia at approximately $2bn per year.

The tightly communal nature of Somali business practices, pooled equity funding models, commercial development that often takes place outside the regulations of the banking sector, and relatively high levels of official corruption in Kenya undoubtedly combine to make Eastleigh an attractive destination for illicit finances (for 2010, Transparency International ranked Kenya as the third most corrupt country in East Africa after Somalia and Sudan). Some pirate money has almost certainly found a home in Eastleigh, though with piracy funds currently coming in at 1/10th of those from remittances (and we’re ignoring for the moment the revenues generated by ongoing business in Eastleigh), it’s more likely that ransom money in Eastleigh is chasing the development boom, rather than driving it. Although it’s far less sexy to talk about hard work and legitimate funds when analyzing a Somali-dominated economy, as I don’t have any plans to sell my services as a Somali piracy expert, my vote is going to have to be ‘no’ on the development via pirate booty hypothesis.

The next article in this series will explore a number of alternative hypotheses for what has driven Eastleigh’s economy, happily complicating the story along the way.

Have your own ideas about what happens to pirate booty? We welcome all ideas, critiques or wildly speculative theories; so don’t be shy when it comes to the comment box below.

Additional resources:

• A good, short exploration of these issues can be found in the Chatham House Briefing Paper, Somali Investment in Kenya, by Farah Abdulsamed (March 2011)

• One of the few press articles that goes after complexity rather than speculative sexiness is by the BBC: Chasing the Somali piracy money trail

• Decent piracy figures and charts can be found on the Blue Mountain Group website

• Bloomberg: Piracy Syndicates Selling Shares to Finance Attacks

• Somalia Report: The Myth of Eastleigh’s ‘Piracy Cash’ Boom (A California-based website, Somalia Report offers excellent coverage of Somali issues)

• Another fascinating article from Somalia Report: How Pirates Spend their Ransom Money

• A respected source on Somali remittances is Anna Lindley’s, The Early Morning Phone Call: Somali refugees’ remittances

• The International Maritime Bureau also publishes detailed statistics each year on piracy, though their reports are only for purchase via their website

• Finally, a wonderful example of the love for excessive detail by the Wikipedia community can be found on their Somali Piracy page

————————–

I found this article to be very interesting, especially after reading the last posting. It was good to find that piracy was not driving the development here. It’s rather exciting to see a place thriving because its people are resourceful and hard working. Again, makes me think of the early Chinese immigrants to the US who must have done the same thing (pooling cash) in order to grow their businesses and gain a foothold in the economy.