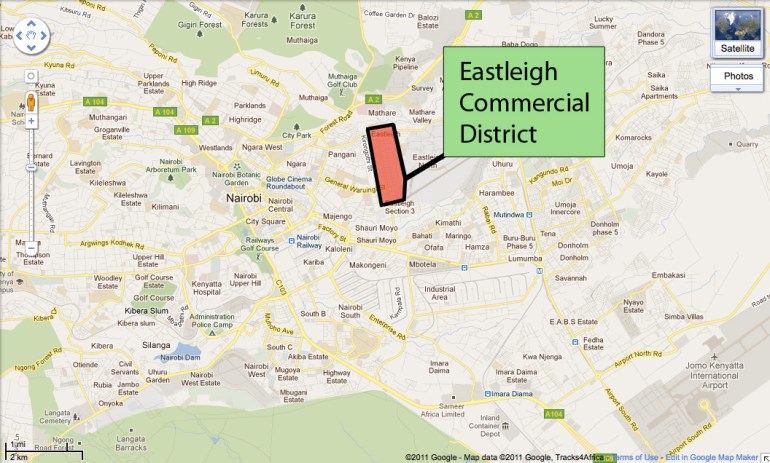

The first of three pieces on economic development in Eastleigh, this article will give some brief descriptive orientation to the neighborhood, with the follow-ups exploring some hypotheses for the rapid economic development.

The first week of research has been a whirlwind of interviews and neighborhood orientation – a stark contrast to last year’s first week spent largely organizing ourselves and preparing for travel. This owes much to Neil’s preparatory work getting a feel for the town, and our luck in meeting an excellent local informant on the first day. While checking out the largest new hotel in Eastleigh, we came across Kaamil, a local cable TV and online newspaper reporter from Mogadishu who’s been working in Eastleigh for the past nine years. Kaamil’s reporting instincts make him fearless in knocking on doors and helping arrange high-level interviews at a blistering pace.

This first report will give a brief description of Eastleigh and some of the economic action in the neighborhood. Our thinking is that getting a handle on the economic dynamics in this neighborhood is a good starting point for contextualizing the motivations and experiences of the Somali diaspora with connections here. We’ve had a number of interviews with business leaders, property developers and retailers, who have all been tremendously helpful in giving us access and information across a range of social levels. Although there’s certainly a lot more to learn about a place as complex as Eastleigh, here’s a basic description of commercial development in the town.

One of the first things to stand out about Eastleigh is the sheer volume of activity. Eastleigh has developed into one of Kenya’s largest commercial districts, with approximately 100,000 residents, more than 30 large shopping malls, thousands upon thousands of retail outlets, and a huge number of hawkers covering the sidewalks and even roadways, all packed into less than one square mile of land.

Somali merchants serve as the primary wholesale distributors for low-end apparel and electronics across the entire region. Every day large trucks are loaded with goods from Eastleigh to supply markets throughout Kenya and as far as Tanzania, Uganda, southern Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda.

Growth has been explosive since the 1991 Somali civil war, and particularly meteoric in the past few years, with new retail and residential space popping up all over town.

Shopping malls have been a particular focus of ours in this first week, as they serve as the hub for activity in the garment and electronics sectors, as well as housing banks, travel agents, cyber cafes, clinics, development and construction firms, restaurants, mosques, professional training centers and more. They’re also a major focus of investment from Somalis here and abroad.

The mall concept originated with the old Garissa Lodge, which was the main hotel for Somalis visiting the area in the early 90s. Somali merchants would display goods on their beds during the day for prospective buyers, and eventually the entire hotel developed into a series of small shops operated out of the hotel rooms. This basic model has been transported into today’s malls filled with tightly packed small shops. The micro subdivision model of retail space offers low barriers for market entry and a wide selection of goods within each shopping mall.

Wholesalers / retailers such as these in the Sunlight Mall cut costs by consolidating retail and storage space

Until recently, the banking system serving Somalis in Eastleigh was virtually non-existent, which meant that most real estate projects here have been realized out of equity rather than debt. Property developers will often create a funding structure that is a hybrid of Somali community investment practices and Islamic finance models. Networks of Somalis who know and trust one another pool funds, thus circumventing the need for external financing from banks with security taking the form of existing assets. Such models can be quite similar to the Sharia’a-compliant financing vehicles of limited partnership (Mudaraba) or joint venture (Musharaka). The idea behind the Sharia’a-compliant financing is to enable Islamic investors such as local Somalis to increase their return via leverage with borrowed capital without breaking Sharia’a rules that prohibit charging interest, the use of hedging instruments, or involvement in certain sectors like gambling.

In line with such practices, a developer may raise capital by charging prospective shop owners a high upfront fee called ‘goodwill’. Definitive numbers for the neighborhood as a whole are hard to come by, but our informal surveys indicate that an upfront non-refundable payment of 25 to 40 times the monthly rent is typical for a 5-year commercial property lease. While the practice of charging ‘goodwill’ generates no small amount of controversy among shop owners, property developers claim that such fees are what allow them to realize property development projects out of equity in the absence of widespread access to traditional banking services.

There is also considerable investment in hotels and residential apartments, which along with the shopping malls are steadily replacing the older single level courtyard-style residences in Eastleigh.

A small sample of historical development at the southern edge of Easleigh illustrates the pace of new construction in just the past five years. In that time, property prices have doubled in most areas, and have jumped by nearly 500% in some places.

Satellite view comparison of development in southern Eastleigh 2006 and 2011 (Click on image for enlarged view)

Despite a new trend towards finished glass facades, most construction is generally of basic quality, and construction sites tend to be relatively inefficient and labor intensive.

Overhead view of construction site. All concrete is mixed by hand into a single mixer at the lower right, then raised by winch and delivered by wheelbarrow.

One property developer told us that such properties usually take a year to move through the permitting process (in which bribes play a central role), and then another 18-24 months for actual construction.

The rapid expansion of banking outlets in the city and other higher tier economic services such as commercial insurance providers, along with newer projects built to a higher standard, such as the Grand Royal Hotel, indicate that Eastleigh may be reaching a more advanced stage of economic development due to market saturation and attendant competition.

The big question is whether market saturation will lead to a general slowdown or bursting of a property market bubble, or whether the next stage will entail slower, but more sustainable growth. Some new shopping malls are sitting on significant retail vacancies, but this could be due to an over-saturation in specific markets like clothing retailers which favor these small sub-divided retail spaces, while other sectors such as financial services and healthcare seek more appropriate locations.

The primary complaint from residents and developers alike is the sorry state of local infrastructure. Paved roads and municipal services like garbage collection are nearly non-existent, leading to the local business association to file a suit against the Nairobi City Council.

Water and electrical services are also woefully inadequate for the level of growth in this area, and collections of household water jugs, along with large diesel generators powering shopping malls are common sights. Claims of government corruption and speculation that fears of competition threats to the downtown business district are behind the lack of infrastructure investment are common among local residents. That said, the Kenyan High Court recently ruled that the City Council is barred from collecting taxes from 3,000 businesses for not providing municipal services, and there is talk now of large-scale infrastructure projects slated for Eastleigh later this year.

The next post will explore the common argument / local rumor that the boom in commercial development in Eastleigh is driven by ransom funds from Somali piracy.

If you have any questions or ideas to add to this post, please feel free to comment below. We’re just getting started with our investigations and analysis, and so welcome any insights you might have to offer.

————————–

Inspite of how slow they’re building (mixing cement by hand!), it’s impressive the amount of development in such a short time. The pictures are great. They remind me of a number of the gritty, growing cities I’ve visited including places in Taiwan when I was young.